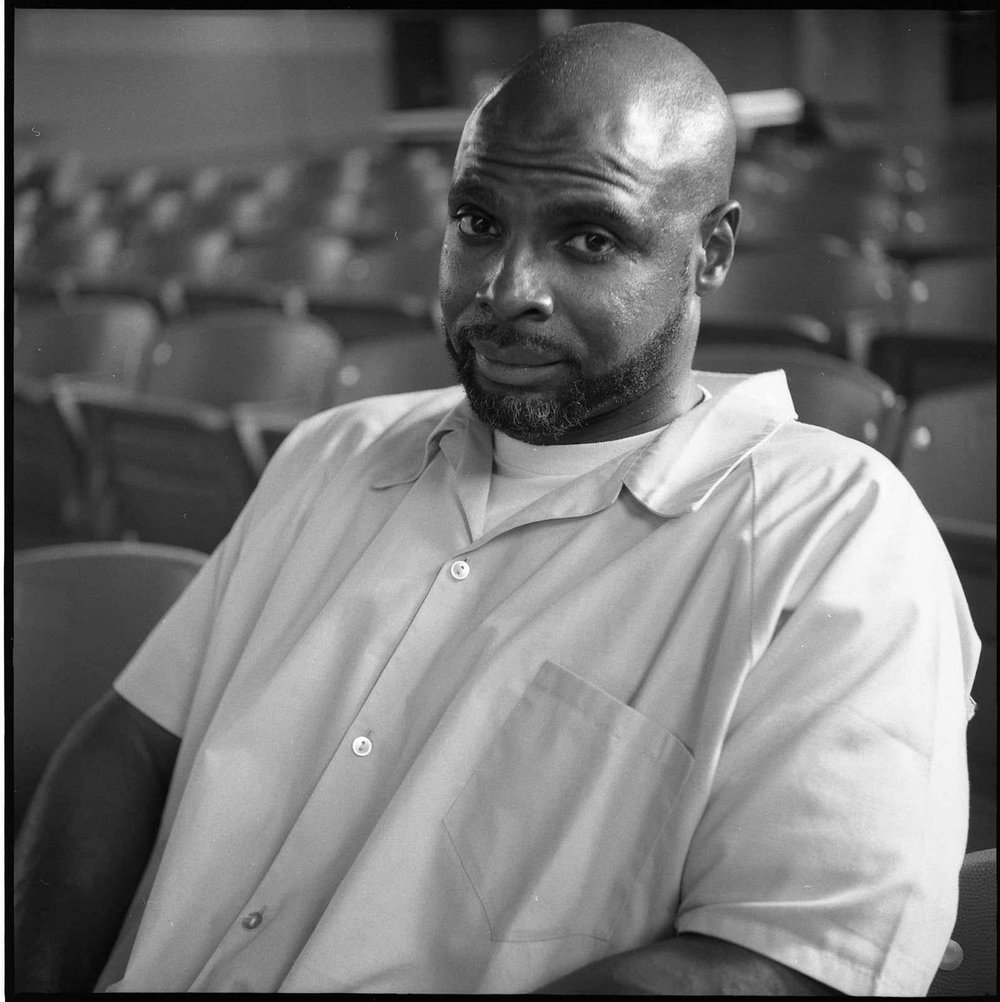

Portrait by Justin T. Jones

This piece, written by Cedric Walker, also known as “IT HAS BEEN CED,” an incarcerated community member in the Stateville Think Tank, reflects on the legacy of the civil rights movement and the ongoing challenges Black communities face, particularly in Illinois. Cedric questions why incarcerated individuals are denied the right to vote, drawing parallels to the oppressive practices of the Jim Crow era. He argues the necessity of passing legislation that allows people in prison to vote is a step toward justice and aligns with the national sentiment supporting their reintegration into society.

Growing up, voting was never communicated to me as my communal responsibility. I grew up hearing about the exploits of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders who marched in the name of equality to secure the right to vote for Black people in the Jim Crow South. However, the legacy of the civil rights movement – its influence once only a distant notion in my mind – was difficult to see in any part of my history or present.

Now, it could be argued that significant change has occurred since the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. I wouldn’t disagree. Conversely, it could be equally argued that certain socio-political conditions of Black people in Illinois, regardless of the right to vote, remain unchanged since Jim Crow. For example, 55% of people incarcerated in the state of Illinois are Black, even though Black people make up only 15% of the state’s population. This makes Black people disproportionately represented in our legal system.

The common theme between then and now is that disenfranchised Blacks remain within the fabric of the overall socio-political discussion regardless of their social location.

It would appear then that fighting for the right to vote Jim Crow’s influence out of the system in the South merely created the path to vote the new Jim Crow – mass incarceration – into existence nationally. Thus, when the question “Why should people in prison be allowed to vote?” is raised, I wrestle with whether that question has legitimacy for one reason: over half of the country (56%) supports restoring the right to vote to people in prison.

Since half of the country supports prisoners receiving the right to vote, the question of legitimacy compels me to ask questions of my own. For example, what kind of society would be opposed to an incarcerated person learning how to legally and peacefully participate in civic engagement? Isn’t correction of this sort the point of incarceration? We know 95% of incarcerated people return to their communities. What would be unconstitutional about prisoners having the right to vote for a candidate who pledges to build infrastructure for returning citizens?

Some returning citizens have mothers who were incarcerated. Women are the fastest-growing demographic in prisons, and 80% of women who are incarcerated are mothers. A mother should not be precluded from casting a ballot for the candidate who offers the possibility of her children not being directly impacted by the criminal justice system as she had been.

Ultimately, denying people in Illinois prisons the right to vote not only resembles a time in our history when socio-political conditions all but mandated the criminal justice system’s power to render people helpless in affecting the future of their community. However, it also stands in opposition to the national sentiment. Incarcerated persons have a place in our society because of the prospect of returning to our communities and the fact that their absence negatively impacts the youth therein. Was the right to vote created for the person? Or was the person created with the right to vote?